[ad_1]

In an article revealed in Veja journal, the political scientist Fernando Schüler writes in regards to the award-winning American journalist Glenn Greenwald.

More particularly, about how illiberal individuals goal the previous Intercept man.

The purpose? Glenn defends freedom of speech as a common precept, whether or not for “Trumpists, Lulists or Bolsonarists”.

“What struck me most was his unconditional defense of principles, something uncommon around here,” says Schüler.

“Whoever defends a principle,” in response to Glenn, “is not on the side of any faction, left or right.”

The political scientist recollects that after advocating freedom of speech for “right-wing” parliamentarians, journalists, and influencers, Glenn was branded a “Bolsonarist.”

“The non-argument our lazy thinking throws up against anyone who risks diverging from the dominant tribe,” he famous.

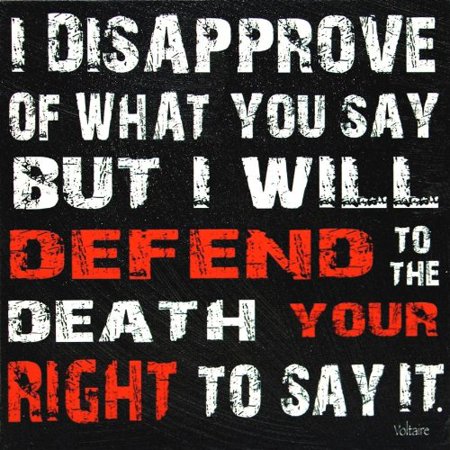

“Here in the tropics, it seems hard to accept the simple idea that one can disagree 100% with an opinion, but defend ‘to the death’ its right to expression.”

In the textual content, Schüler cites one other argument utilized by bigots: Glenn defends “American prerogatives,” and the legal guidelines of that nation don’t apply to Brazil.

“There, too, there is a mistake,” he famous. “Who says that our Constitution authorizes prior censorship? Or fails to protect due process, the adversarial process, which includes lawyers’ access to case records?”

“Or who knows the inviolability of our representatives, inscribed in its Article 53? More than Brazilian, these are civilizing prerogatives, proper of any republic worthy of the name.”

But it doesn’t cease there.

According to the columnist of Veja journal, there’s additionally a 3rd trick, which consists of associating those that defend freedom of expression with the assist of “these vandals”.

Read: the protesters who dedicated acts of vandalism in Brasilia. “It’s the logic of all or nothing,” he said.

“Either you uncritically defend any repressive measure by the state, otherwise you fail to ‘defend democracy’.

Absurd logic.

One should differentiate who makes use of violence, blocking roads or invading a palace, from those that merely situation an opinion on social networks, despicable as it could be.

Differentiating these items is a necessary a part of the boundary separating an authoritarian regime from a liberal democracy.”

For Schüler, Glenn’s view “sits in a narrow band these days, at once critical of authoritarian views that spring up in society and of the authoritarianism that comes from the state, via infringement on individual rights.”

This would find yourself “feeding back political radicalism”.

The columnist mentions the checklist of politicians and influencers banned from social networks in Brazil.

“One of them was Nikolas Ferreira, the country’s most voted young deputy,” he recalled. “What exactly was his crime? He asked that investigations into the January acts involve federal officials as well. He danced.”

“A deputy should be inviolable in ‘words, opinions, and votes,’ as the Constitution says, to even ask for the investigations he deems due. In today’s Brazil, he was silenced. Most laugh. Others shrug.”

“Still others walk in fear. These things always arise when we accept that it is up to the State to decide about the truth when the crime of opinion comes into play, and when we admit that the courts, which should preserve the law, act with ‘audacity’ before the law, as I read around.”

According to Schüler, respect for common ideas was essential within the delivery of the fashionable thought of tolerance and particular person rights.

The story of the thinker Voltaire and the martyrdom of Jean Calas, a Toulouse service provider accused of killing his personal son in 1761, present this.

“Calas was 63 years old and a Protestant in a city marked by Catholic fanaticism,” the columnist recounted.

“The charge was flimsy, but he was sentenced to torture and death. Every part of his body was broken. They stuck a funnel down his throat, pouring 17 gallons of water.”

“Then they put him on the wheel, where he was stretched to bursting point. He endured it all, repeating that he was innocent. His obstinacy touched Voltaire’s soul.”

“He saw in it all the century’s barbarism, but also the flame of individual dignity. Convinced of his innocence, he makes it a matter of honor for himself to rehabilitate the memory of Jean Calas.”

What is charming about this tragic episode, says the political scientist, is Voltaire’s “absurd” perspective.

“Voltaire was an established man, had just published the Candide, and was about to inaugurate his Ferney Castle. And he didn’t even know Jean Calas.”

“Nevertheless, for two years, he devoted himself to reopening the case simply out of obedience to a principle. Finally, he succeeded.”

“In March 1765, three years after the ordeal, the judges in Paris reviewed the conviction, and Louis XV received Calas’ widow at Versailles.”

“Following this, Voltaire wrote his Treatise on Tolerance. It states simple principles that are still valid today: the idea that everyone deserves a fair trial, and that tolerance is the possible way for us to live in peace and prosper.”

“And that we must overcome fanaticism, that ‘dark superstition which induces weak souls to impute crimes to anyone who does not think as they do.’”

Schüler believes that politics replaces faith because the “public passion.” “Voltaire’s message remains: by giving up certain principles, we are left only with the uncertain universe of instincts, of our preferences and precarious judgments about good and evil.”

“If in Brazil today we scold a journalist for defending the freedom of expression and the right to due process, it is because we have a problem,” he noticed.

“If we passively accept the return of prior censorship, the banning of journalists and members of parliament from the Internet, or even worse things like the blocking of bank accounts, economic pressure, censorship of broadcasters, and even imprisonment for the crime of giving an opinion, it is because we have a very complicated problem.”

“Something that will not be solved by an instrumental reason, which says ‘we need to stretch the Constitution a bit because there is an enemy to be defeated’.”

The political scientist concludes the textual content by saying, “to remember Voltaire is to take the opposite route, which binds us to certain principles made precisely to curb our instincts.”

According to Schüler, “principles that are not ‘American’, but are all there, in the Brazilian Constitution and laws, whose respect is the only possible way to reconcile this country that sometimes we barely manage to recognize.”

[ad_2]