[ad_1]

Jo Ann Schmidman, Megan Terry, and their canine.

You might not affiliate artists within the vanguard of American experimental theatre with Omaha, Neb., however that’s the place Open Theater alums Megan Terry and Jo Ann Schmidman at present reside.

Few residents of the downtown neighborhood they reside in doubtless find out about their revolutionary legacy or the world-class artistic circles they ran in. To the uninitiated, Terry and Schmidman are only a mildly eccentric lesbian couple with an overgrown entrance yard obscuring their Mother Hubbard residence.

Visiting them at their art-filled, book-lined abode, you’re greeted by the three massive canine Schmidman trains. The girls share the straightforward rapport of longtime companions who end one another’s sentences. Terry, nonetheless an important presence at 89, fixes on you with a mushy however looking out gaze. Schmidman, 74, regards you with inscrutable curiosity. Just as neither has a have to be within the highlight anymore, there’s no trace of remorse that they largely walked away from the theatre two-plus a long time in the past.

“The art of living,” Schmidman says, turned their artistic expression. Their canine, gardening, understanding, and coping with enterprise affairs is a lot to occupy their time. Terry’s performs nonetheless get produced, and new translations proceed to be made.

Terry, initially from Washington state, was impressed to write down performs after studying the work of Samuel Beckett and Gertrude Stein. In Seattle she revived the Cornish Players on the Cornish School of Allied Arts, however quickly confronted board-driven challenges to her imaginative and prescient. So she packed up her Chevy for New York City.

“I said, ‘Goodbye—I’m going someplace else, where I can do what I want to do,’” she remembers.

Her break got here within the late Nineteen Sixties when Terrence McNally chosen her play Ex-Miss Copper Queen on a Set of Pills to accompany one in all his personal performs on a invoice off-Off-Broadway. Joseph Chaikin and Michael Smith noticed it. Terry remembers that Chaikin “hated the production but loved the writing. He said, ‘We’re thinking of starting a theatre and we’re looking for writers, are you interested?’ There they were, my dream boys, and we were off to the races.”

With Chaikin, Smith, and others she co-founded the Open Theater, which broke with custom by celebrating subversive, non-linear work. La MaMa’s Ellen Stewart championed this new wave of playwrights, who upended theatrical and social conventions and uncovered injustices. Terry quickly turned a darling of the avant-garde, alongside such luminaries as María Irene Fornés, Susan Yankowitz, Sam Shepherd, and Lanford Wilson. Her items performed Cafe La MaMa and Caffe Cino.

“How lucky we were to be alive and working then,” Terry remembers. “Going to see all these plays by these wonderful writers, God, was inspiring, thrilling. It was like playing a game of, ‘Can you top this?’ Whoever had a new play, everybody was there.”

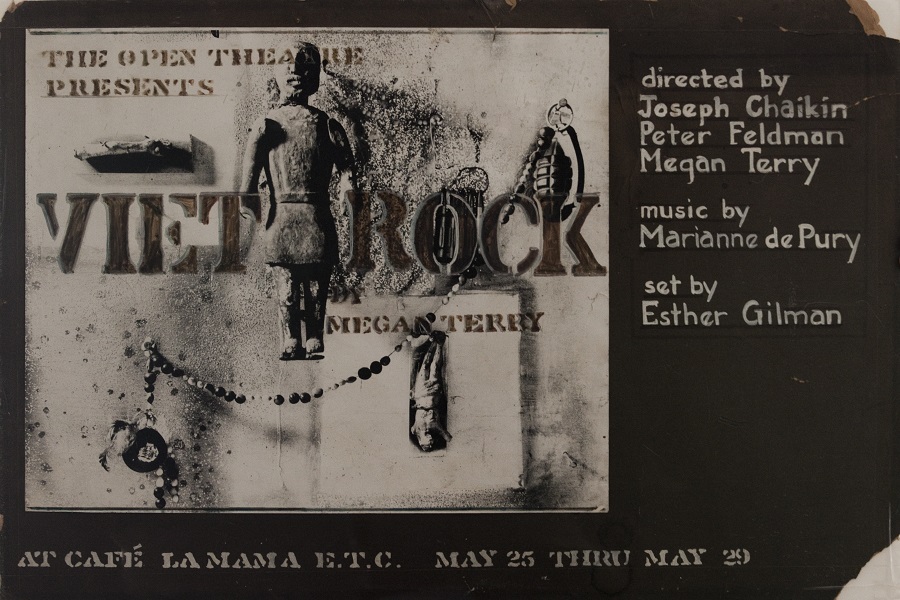

Her Viet Rock, which some think about to have been each the primary rock musical and the primary Vietnam War-themed theatre work, was must-see Off-Broadway within the mid-Nineteen Sixties. It influenced the creators of Hair, who workshopped their musical alongside hers. Experimental icon Robert Wilson recommended hanging recent laundry over the viewers for Viet Rock.

Edgy theatre, Terry stated, was the place to be for those who wished to see artwork that was talking with immediacy to the instances.

“When I did Calm Down Mother and Keep Tightly Closed on a double bill at the Cherry Lane, half the audience hated it and half loved it,” Terry remembers. “They put me up against the wall in the lobby, screaming, ‘What are you trying to do us?’”

“Because it mattered,” Schmidman chimes in.

“It really mattered to the audience,” Terry agrees. “It was an amazing time.”

Schmidman, an Omaha native, acquired bit by the theatre bug attending Broadway touring musicals in New York and Kansas City, Mo. After stints in kids’s theatre and an adventurous wing of the Omaha Community Playhouse, she studied at Northwestern University and Boston University. But earlier than lengthy she was drawn to the work of groundbreakers like Terry and Chaikin. In 1968 she based the Omaha Magic Theatre, modeling it on the Open Theater.

Starting Omaha’s first experimental theatre at age 20 didn’t appear dangerous to her at time time, she says. “There is something incredibly expansive about this area and about the people that live here,” she causes. “The extremes of temperature, I believe, allow extremes of creation.”

She quickly joined the ferment of the NYC scene as an Open Theater actor, performing within the firm’s closing play, 1973’s Nightwalk, co-scripted by Jean-Claude van Itallie, Sam Shepard, and Terry. She toured the world with it. She additionally starred in Terry’s Obie-winning play Approaching Simone.

The two girls’s adventurous spirits discovered one another at a 1969 anti-war rally on the Boston Common. Schmidman, nonetheless a BU scholar, was doing guerrilla theatre carrying a tin foil masks, whereas Terry, godmother of radical girls playwrights, was a visiting artist on her method to hear Howard Zinn converse. Recalls Terry, “Jo Ann was in the middle of a wood on the way to this massive protest and her mask came off and fell down. I picked it up. ‘Do you want to keep wearing this?’ Her hair was clear down to her bottom. Fantastic.”

Making Magic in Omaha

The pair lived collectively within the Village and held workshops in Terry’s loft. During breaks from her Open Theater schedule, Schmidman revisited her Magic Theatre in Omaha. Terry typically joined her. When the Open Theater closed, the 2 settled within the Midwest to create new work collectively, with Terry as resident playwright and Schmidman as resident director. Both acted in productions. Schmidman developed right into a playwright in her personal proper.

Decades earlier than immediately’s motion for gender parity within the theatre, Terry and Schidman produced their very own unique work and that of others, like Paula Vogel (Baby Makes Seven) and Fornés, who got here to Omaha to direct her play Mud.

Terry embraced making new theatre in Nebraska. “I was very interested in this community and what these people were about,” she says.

Schmidman says she knew Terry can be match. “She came to work with a company. That was her calling—to make theatre for others. You sort of couldn’t do that in New York as well or as easily.”

Besides, Terry explains, “the magic” was wherever they hung their hats. Their community-based, imagistic theatre, rooted in exploration and in presenting issues in boundary-pushing methods, discovered receptive audiences in that conservative state. Feminist, queer, and different social themes permeated the work, although they are saying the theatre by no means branded its reveals with identification politics labels.

“We, believe me, didn’t name it,” Schmidman methods. “We were honest, truthful. But it wasn’t a gay statement when we did Babes in the Big House with an all-male cast. In my brain, it became one. We wanted to do a play about women in prison and our company was practically 80 percent male at that time. So what are you going to do? The men did it and it was fabulous.”

“The audience could understand what women go through by seeing men go through what women did,” Terry says.

“We would never proselytize,” Schmidman continues. “I wasn’t interested in political theatre per se; I was interested in making it very personal, then it became political in a stronger sense. I think that’s what all of Megan’s plays absolutely have. We always built theatre…”

“…that dealt with our deep feelings and deep observations of the world,” Terry interjects, ending her accomplice’s thought. “And what we had to live with. It was about everything—it was about being a human being.”

The girls toured their work throughout Nebraska, the Midwest, in addition to nationally and internationally, and traveled extensively to do workshops, residencies, and lectures at faculties and universities.

But whereas they felt free to create edgy work in Omaha, their theatre by no means obtained the complete assist it might have wanted to proceed. The Magic Theatre formally closed in 1998 after 30 years in operation; each girls say they have been exhausted by limitless fundraising cycles, and native company assist by no means materialized. Though they have been by no means informed to their faces, presumably the city’s buttoned-down sorts regarded their performs as too far out.

“It didn’t get easier,” Schmidman says. “There was no sugar daddy saying, ‘Oh, what brilliant work, don’t think about writing another grant, I’ll take care of it.’ It never happened.”

But Terry continued writing and accepting commissions, whereas Schmidman consulted rising artists. Looking again on all of it now, from the vantage level of 2022, with the reversal of Roe, the specter of Trumpism, and every day stories of mass shootings, even these two surrealists discover the actual world a bit—properly, surreal.

“Can you believe it?” Schmidman marvels. “I mean, you can’t do theatre about it, even because it’s not believable.”

“It’s beyond absurd,” says Terry.

Schmidman continues: “My therapist says it’s the truth we have to understand before we can change something or work on changing something. Instead of just saying it’s out of whack, which is my inclination, we have to embrace it as the truth.”

She wonders if these “weird times” would possibly “give birth to a new theatre. That’s what happened in the ’60s, right?”

“We have to start all over again,” solutions Terry.

One place to begin: not essentially in New York. Terry says her former colleague, Joe Chaikin, used to lament that an excessive amount of theatre was about actual property. “That’s why he hated Broadway. He wanted to destroy Broadway. That used to be Chaikin’s monologue.”

“A vital new theatre,” Schmidman says, “certainly doesn’t need to be tied to real estate. There are new dumps in every city where they can roll up their sleeves and get to work. It’s hard work is the thing.”

Omaha rents weren’t as prohibitive as New York’s, besides, Schmidman says she typically negotiated rent-free stays at her constructing. Company members typically lived communally, and Terry dumpster-dived to salvage meals from a four-star French restaurant.

There are different ideas that small theatres may take from Magic’s instance. On constructing an viewers: Schidman says that the metal fabricators and paper producers whose merchandise have been utilized in productions “wanted to see how their goods were transformed into art,” Schmidman stated. “We built theatre around them.”

Another audience-loyalty tip: They let of us pay as soon as and see a present a number of instances.

But they didn’t simply make theatre in Omaha for the low rents. They hyperlink their DIY ethic to the creatives, dreamers, and doers of their households.

“The pioneering spirit and the quest to work with your own hands, out of your own soul, is an Omaha, a Midwestern trait, and that’s exactly the kind of theatre I was interested in doing,” Schmidman says. “It didn’t have anything to do with being radical; it had to do with being homemade and what is inside of people. It wasn’t about shocking people; it was about giving them a vehicle to reflect, a way to understand one’s self better, to go on a spiritual journey.”

That self-discovery, crucially, could possibly be shared with others.

“For us, it was thinking if we look deeply enough inside, we could share with audiences something that would go deep inside them,” Schmidman says.

That looking out spirit knowledgeable not solely the work on their stage however how they ran the theatre.

“What part of patriarchy do you take on?” Schmidman asks rhetorically. “Having a board that tells you what to do—is that a part of corporate America the arts should subscribe to? I don’t think so. I knew that we couldn’t go there. We would have sold out. They would have determined what was on that stage.”

She advises theatremakers to stay impartial. “They need to get out there, roll up their sleeves, start making their art, and not have fat-ass boards. Don’t give ’em that power.”

Theatre, they recommend, might be a part of therapeutic America’s divisions. Says Terry: “We have to reconcile the different groups and accept one another.” Schmidman provides: “Theatre is the great unifier. If we were still making theatre, the pieces would be about living and loving.”

An archive of Magic Theatre’s work is housed on the University of California-Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, and Terry’s New York performs are a part of the Open Theater archive at Kent State in Ohio. The 1975 guide Three Works by the Open Theater contains Nightwalk and manufacturing stills.

The 1992 guide Right Brain Vacation Photos chronicles 20 years of the Magic Theatre.

Leo Adam Biga (he/him) is an Omaha-based freelance author and the creator of the 2016 guide Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film.

Related

[ad_2]