[ad_1]

Arin Arbus. (Photo courtesy of Theatre for a New Audience)

For greater than a decade, Arin Arbus has directed classical productions of participating readability and heat, notable for scrupulous consideration to the textual content and a welcome absence of gimmicky modern trappings. But the performances formed by her fingers, mainly at Brooklyn’s Theatre for a New Audience, the place she is resident director, by no means look like museum items; quite the opposite, they’ve a freshness and vitality that stems from her conviction that nevertheless way back the actual piece was written, it has one thing to say to audiences at the moment.

“She always treats the playwright’s ideas as absolutely of the moment,” mentioned TFANA’s founder, Jeffrey Horowitz, with whom Arbus labored for 10 years as affiliate inventive director. “Whatever she identifies as driving her to do this play, whatever she feels is at the core of the play, she sees in society right now.”

Her curiosity in chatting with the second has prompted Arbus to department out from the classics in recent times, first with 2019’s Broadway revival of Terence McNally’s Frankie and Johnny within the Clair de Lune, and now with the New York premiere of Des Moines by Denis Johnson, which begins performances at TFANA’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center on Nov. 29. Johnson, finest identified for the novel Tree of Smoke and the brief story assortment Jesus’ Son, has additionally written quite a lot of performs, although that is his first main New York manufacturing. Arbus mentioned she’d been fascinated with directing Des Moines—a five-character play about an impromptu gathering within the metropolis of its title that turns into one thing a lot deeper and stranger—since she learn it in 2013. She mentioned she thinks the play exhibits proof that its creator “was thinking about Chekhov and Shepard and even Shakespeare; he leans on those writers, he borrows from them, and he makes something that is utterly his own.”

But earlier than she acquired round to this departure, Arbus was constructing one thing of her personal. She got here galloping proper out of the gate with a 2009 manufacturing of Othello that garnered a rave from The New York Times, which mentioned that Arbus dealt with Shakespeare “with the kind of artistry we always hope for but rarely find.” Added Horowitz, “It was the most potent debut of an artist we’ve ever done. The response was electrifying and immediate; the entire run sold out literally in a couple of hours.”

Arbus helmed six extra Shakespearean productions at TFANA over the subsequent 13 years, plus an Obie-winning revival of Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth and a double invoice of Strindberg’s The Father and Ibsen’s A Doll’s House. She did high-quality work on all of them, however she demonstrated a particular affinity for the Bard. The issues and contradictions of such notoriously tough performs as Measure for Measure and The Winter’s Tale had been embraced somewhat than tidied up; requirements like King Lear and Much Ado About Nothing felt newly minted, their themes quietly rising from the characters’ private relationships.

Still, she instructed me that when she first got here to TFANA in 2007, “I had no interest in Shakespeare. I knew nothing about Shakespeare, I had never studied Shakespeare in high school. I thought Shakespeare was for scholars, highly educated people who specialize in Shakespeare. And I sort of thought Shakespeare onstage was boring.”

It was the Royal Shakespeare Company’s legendary voice director Cicely Berry, a longtime TFANA collaborator, who shattered these preconceptions. “She did an annual workshop exploring how actors and directors could work together to bring Shakespeare’s words alive through language,” Arbus recalled. “She was a Marxist, she hated snobbery, and she believed that Shakespeare belongs to everyone—that everyone can access the meaning of those words even if they don’t understand the literal meaning. There was a deeper meaning in the sounds of the words; you had to speak the language aloud in order to fully grasp the poetry and meaning. It was a shocking discovery to me that actually Shakespeare is writing about the world we live in, the people that I know, and me!”

Before she arrived at this revelation, Arbus went by means of the apprenticeship interval acquainted to most fledgling administrators, aiding extra established administrators whereas making use of what she was studying in tiny Off-Off-Broadway productions. Assigned to help Gerald Gutierrez whereas she was a directing resident at Playwrights Horizons, Arbus discovered her first mentor. “He taught me so much; he was amazing at text analysis, and he was amazing with comedy,” Arbus mentioned. “I took notes for him, and they were so technically precise; they taught me about what an actor needs to do to land a line, to get a laugh. He was a great teacher and friend.”

She adopted Gutierrez to Lincoln Center for a manufacturing of Dinner at Eight and was slated to help him at Theatre for a New Audience on Engaged, a Nineteenth-century farce by W.S. Gilbert, when Gutierrez died all of the sudden from respiratory failure as a result of flu.

“It was devastating,” Arbus mentioned. “It was a total loss of my friend, my teacher, and my employer; he had productions that I was going to assist him on for a couple of years in the future. I was in a fugue state.” Horowitz, honoring Gutierrez’s insistence that Arbus be his assistant on Engaged, saved her on to help the brand new director, Doug Hughes, then employed her for normal workplace work and to help different administrators. “I kept saying, ‘Arin, if you want to direct, why don’t you come to me and say, “I want to do a showcase?”‘” he recalled. “She said, ‘I want to do something that’s meaningful,’ and one day she told me she was volunteering on weekends at this theatre program [Rehabilitation Through the Arts] at an all-male prison a three-hour drive from New York and directing a play there!’”

She had been disenchanted by her experiences within the fringe and business theatre, Arbus mentioned of that point.

“I was directing these little productions that nobody really wanted to be in, and nobody wanted to attend,” she mentioned. “I was also assisting on some Off-Broadway shows, and I saw great work that would get a bad review and then nobody would come, or it wouldn’t be good and it would get a great review and everyone would love it. There was something about the capitalist structure that was sucking the life out of it. The amazing thing about working with Rehabilitation Through the Arts at Woodbourne was that the men who were in that program were there because they wanted to learn about themselves and the world, and they were giving up a lot of time and a lot of other things to rehearse a play. I thought maybe if you take capitalism out of the equation—you can’t take capitalism out of the equation in a prison, but just in terms of doing theatre—and if you are coming to it to discover something about yourself and the world, it would be alive in a different way.”

It actually was, Horowitz found when he attended Arbus’s electrifying manufacturing of Of Mice and Men within the jail lunchroom. “I still get chills talking about it,” he mentioned. “The power these prisoners conveyed to those watching! During this play, where they’re talking about an accidental murder, about losing a home, about a mercy killing—this audience of prison guards, administrators, and inmates, they knew what this play was about. It was incredible, and afterwards I said, ‘If you can do this, you’re ready to direct a play for us. It must be Shakespeare: pick a play.’”

Arbus picked Othello.

“I read a lot of Shakespeare I had never read before, and I remember thinking, ‘I wouldn’t know what do with that, I wouldn’t know what do with that,’ and then I read Othello,” she mentioned. “I didn’t know how to do it, but I connected with the territory. I felt I understood his predicament: When the person you love and are anchored to in life betrays you, then everything comes apart. I had some core suspicion about that.”

It’s attribute of Arbus’s model that it was a connection between a private and an existential dilemma that attracted her to the play, and that she describes her preliminary perception into it as “a core suspicion.” She shouldn’t be a director who arrives on the first studying with a imaginative and prescient of the play that she desires her forged to execute; her guiding ideas are investigation and, above all, collaboration.

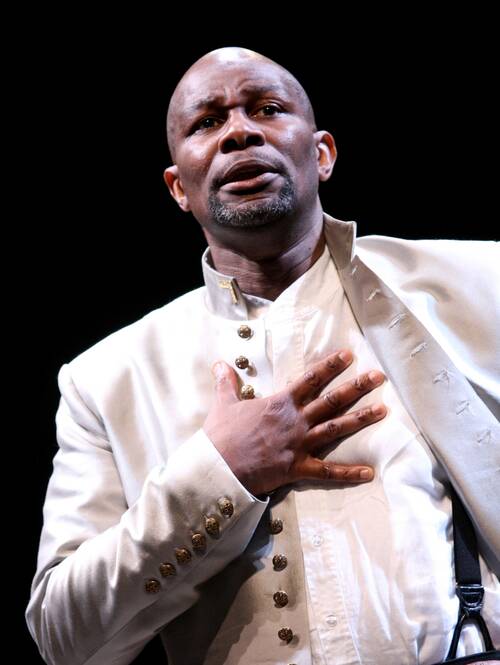

“Arin comes to a play with the right questions,” mentioned John Douglas Thompson, her Othello in 2009. “Sometimes they don’t have answers, but the question is posed, and we will find the answer as a cast. It becomes a collaborative effort, which to me is the main principle of doing theatre.”

He was skeptical, Thompson admitted, when a novice director making an attempt her first Shakespeare requested him to play a task he had carried out 5 occasions earlier than. “But Arin brought this newness that gave the play more possibilities than I had imagined. She opened up the play in different ways. She recalibrated and shifted the focus to the women in the play in a way that I thought was unique and absolutely necessary. It gave Othello more of a focus dramaturgically and allowed me to expand my performance as I never had before.”

Thompson went on to do 4 extra performs with Arbus (thus far), describing himself as “her No. 1 fan.” He continues, “Arin gives all the actors in a production great liberty and great agency—not just the leads, but the whole cast. Everybody gets to participate in the story-making, and that creates really interesting productions. When I am working with Arin, I always feel that I am going to have a huge encounter that is going to make me a better artist. She is very much focused on clarity, and she knows she’s responsible for that, but she gets to that clarity by allowing the artists to go places with the role and the material they may not have gone before. Then she looks at the raw material you put out there and helps you sculpt it so it’s clear and concise and plays into the larger ideas of the piece.”

“The thing I’m interested in is collaboration,” Arbus mentioned. “I feel you have to not know the answers in order to make discoveries. A good process for me is when we are all unearthing what is at the core of the play.”

To her thoughts, the viewers is part of that discovery course of, and she or he enjoys studying from New York City public faculty college students’ responses to her Shakespeare productions. “If it’s good, they are the best audiences; if it’s bad, they will let you know. I believe that if the work is really good, it will reach out to everyone. Theatre is a public forum; I’m not interested in making work for a limited group.” Creating theatre in a jail for six years, in addition to directing The Tempest at a refugee camp in Greece in 2019, had been necessary to her as methods to achieve out to audiences with out entry to business theatre.

All this work has ready Arbus for her journey to Des Moines, a play she described as “beautiful, startling, raw, theatrical. Without a doubt, the play is challenging.” While she famous the affect of Chekhov and Shepard, she added, “The form itself is filled with mystery; Denis keeps pulling the rug out from under us. Des Moines refuses to comply with traditional dramatic structure, but that I think was Denis’s point: Life isn’t like that.”

Likewise, thus far Arbus’s profession has solely appeared to comply with a recognizable sample. She instructed me that she feels “a little bit pigeonholed” by her popularity for guiding classics, including, “I would like to direct a musical, I’d like to direct for film and television, I want to work more with living writers. I’m hungry to be doing all kinds of work.”

Wendy Smith (she/her) is a author based mostly in Brooklyn.

Related

[ad_2]