[ad_1]

Ghost gentle at New York City’s New Victory Theater. (Photo by Jomary Peña)

Happy Halloween! As American Theatre has executed since 2016, we’ve collected one other batch of haunted theatre tales from throughout North America. We hope this yr’s anthology of ghost tales makes for an exciting addition to your assortment of vacation treats.

Dime Drops, a Blue Lady, and a Mystery Bathroom

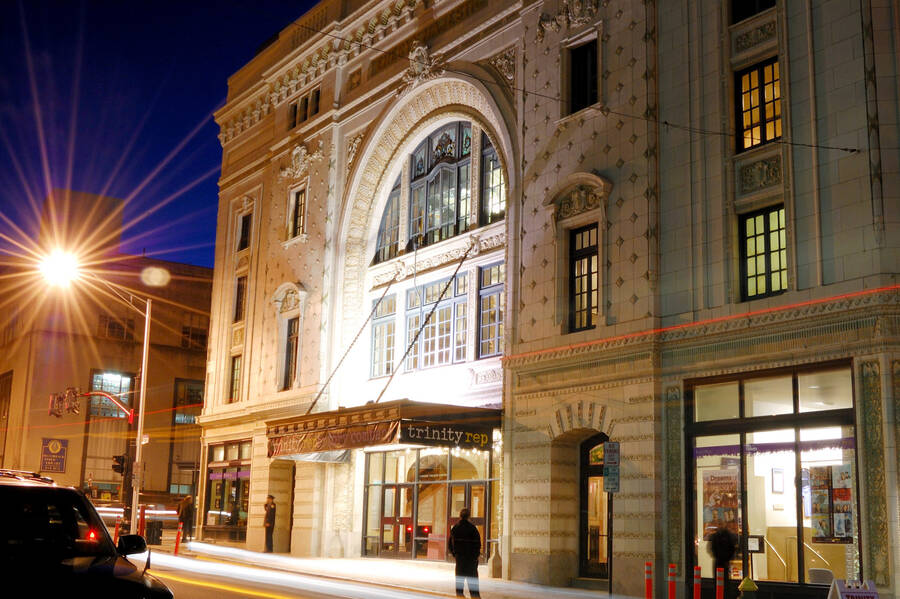

As readers of this collection know, theatres with probably the most historical past usually have probably the most ghost tales. Trinity Repertory Company’s advanced in Providence, R.I., the Lederer Theater Center—which opened its doorways in 1917 because the vaudeville home Emery’s Majestic Theatre—is not any exception. Staff members have been observing unusual occurrences in numerous areas for a very long time.

“I have personally witnessed the elevator arriving empty at night between 8 and 9 p.m., as I have spent a lot of time in the voms of the Chace Theater,” says Trinity Rep receptionist Kelly McDonald, who additionally served as home supervisor from 2006 to 2019. “I have also found dimes where the spirit supposedly hangs out in the Dowling Theater on house left.” What’s so particular about dimes? As this system for the troupe’s upcoming manufacturing of A Christmas Carol (itself a ghost story) factors out in a compendium of a few of the theatre’s eerie tales, devotees of paranormal exercise imagine that the unexplained look of dimes indicators the presence of spirits.

The primary keeper of the venue’s ghost tales in recent times is former technical director Karl Orrall—McDonald notes that after he even led a tour for the employees of the entire reportedly haunted spots. Orrall has had his share of spooky interactions himself. Remarkably, he notes, when “someone brought in a ‘sensitive’ and gave them a tour of the building,” that particular person detected the entire alleged sightings with none prior data.

Among the numerous spirits Orrall identifies is the obvious ghost of a kid.

“Often in the Dowling, when you stand onstage and look toward the booth on the corner of your vision, you can see a dark spot, or maybe it is a mass, house left in the middle row,” he says. “Sometimes when it is quiet and no one has been in the theatre, you can surprise it and you will be able to clearly see a small boy standing there. He is dressed in brown pants, a white shirt, and a corduroy cap—and then he is gone. I know several other people have seen him over the years.”

Then there’s the Blue Lady. In the late Nineties, Orrall served as the corporate’s stage carpenter. At that point smoking indoors was authorized, he mentions, “and the stage crew would hang out on the steps outside of the electrics shop and smoke and drink coffee because there is a window on that level.” He continues, “The first time we saw her was at the places call for a show I can’t remember.” As a number of members of the crew ready to maneuver to locations, he says, “we would wait until the actors passed before we would move. Suddenly a translucent, slightly blue woman came out of the closed electric shop door, headed towards the stage door to the Chace Theater. As she passed the window I remember being able to see through her. She was in a hurry and called out the name Laura a couple of times.” I recollects {that a} manufacturing assistant in a chair on the touchdown beneath the greenroom stood up and shouted, “What the fuck was that?” after which ran as much as the greenroom. “Several crew members avoided the back hall for a while. I think we saw her two more times over the next couple of years.”

Orrall additionally recollects one run of A Christmas Carol a few years in the past during which the present “had two casts, two running crews, and two carpenter crews building it. At one point the entire night crew quit, so the day crew had to work some overnight shifts.” At about 3:30 a.m. throughout one in every of these shifts, Orrall went as much as the restroom within the greenroom of the Chace, the place this season’s Christmas Carol will start performances this week. “I pushed open the door, and a man was standing there washing his hands,” he says. “He was wearing a green sweater with a tan Egyptian pattern on the collar with a pair of tortoise-shell glasses tucked into the collar, brown pants, and very shiny brown loafers. I said, ‘Hello,’ and he said, ‘Hello, you guys are here late tonight.’ I said something about the other crew quitting and that this was a huge build. I went into a stall and heard him grab some paper towel.”

Normal sufficient, proper? Orrall continues: “At this point he asked how long I had been at Trinity. I replied, and then he said that the set was looking good and he told me to have a good night.” Silence. “I left the stall and realized that the restroom door was not swinging closed and that I did not hear it close before I left the stall. I ran out after him but could not see him, and oddly thought to myself that I never heard his shoes on the tile.” Orrall provides, “He was not anywhere to be found. I asked the TD if he knew of anyone else in the building, and he told me that everyone else had left. We all avoided the greenroom for the rest of the night. Years later I saw his picture hanging in the lobby; out of respect I will not say who it was.”

Disembodied Voices and Self-Opening Doors

The Rodgers Theatre in Poplar Bluff, Mo., was opened by impresario I.W. Rodgers as a film theatre in 1949, and present Rodgers Theatre supervisor Shanna Eason notes that there have been so many alleged encounters that ghost hunter teams have led excursions of the constructing and likewise conduct in a single day investigations that flip up fairly a little bit of exercise. “I can’t verify the information they share on their tours,” she concedes. “However, we have had some interesting stories and I personally have experienced strange things.”

What sorts of unusual issues? Why, phantom doorways, as lately as final month. “Most of the doors to the theatre have been upgraded to hollow metal doors with panic bars,” Eason explains, so “they have to be opened from the inside by engaging the bar and in most cases, the bolt locks are engaged.” She notes that on a number of events that the theatre’s doorways have been mysteriously open, “and I have to drop what I’m doing to go close them. Our cameras show them opening and closing on their own! I have been laughed at. Most of the time I am alone there, and I thought someone was lurking; however, the cameras show nothing and the voice sounds right behind me.” Eason says she isn’t bothered by these presences: “I have never been scared by any of the activities because I love the history. It has been a good time, for sure!”

The Prankster Performer

Former Broadway home the New Victory Theater, which first opened as Theatre Republic in 1900, has a wealthy historical past, and plainly a few of the memorable figures who’ve trod the theatre’s boards and backstage have by no means left. Actor Tim Dolan, whose love of theatrical ghost tales led him to determine the strolling tour firm Broadway Up Close, feels the construction’s intensive historical past has lot to do with the assorted ghost encounters over time. “It has had its fair share of big personalities that have filtered through its doors,” Dolan says, “each leaving their mark in their own unique ways.”

Colleen Davis, the New Victory’s manufacturing coordinator, has witnessed firsthand the generally mysterious outcomes of these legacies. From her first day on the theatre, working as an assistant stage supervisor on the day of the opening celebration of the newly renamed theatre in 1995, she discovered that the constructing and units in it could behave in unusual methods. “For one whole day, I could not get a lock or a key or a key code or a door to work, the photocopier—nothing worked for me,” she recollects. But when another person tried, every thing functioned correctly. This was earlier than Davis heard any ghost tales concerning the theatre, and he or she thought the constructing one way or the other hated her. But she didn’t surrender, and after freelancing as a stage supervisor for the group for a couple of years, she joined the employees in her present position in 1998.

A yr or so into Davis’s full-time tenure, throughout a renovation that led the wardrobe crew to work from the lure room beneath the stage as a substitute of their common designated house, simply earlier than a efficiency by the Australian group Circus Oz, a bow tie went lacking. The crew had final seen it on the performer’s dressing room desk. “And it’s not there,” Davis recollects. “We hunted, hunted, hunted—couldn’t find it.” Eventually, a search celebration composed of Davis, the stage supervisor for Circus Oz, and the New Victory’s wardrobe supervisor gave up and determined to start out the present with out the tie. Then, because the three of them had been “walking past the wardrobe room, there was a stack of metal shelves. There was a plastic bin that actually shot out and flipped upside down, and fell on its lid,” Davis provides. The wardrobe supervisor “picked up the bin, and on the floor was the bow tie, and we all said, ‘Thank you,’ and went on with the show.”

Davis says that this turned a sample: An merchandise would disappear from one of many dressing rooms, they’d go on the lookout for it, and “right when we’d give up, that’s when it would be refound somewhere else. Or maybe right where we’d looked.”

That wasn’t the one time a bow tie went lacking and reappeared. Sharlon Wilson, the New Victory’s wardrobe supervisor at the moment, recounts an analogous incident. “I believe it was 2001, I put a bow tie on a rack onstage, and I went to the restroom, and when I returned it was gone,” she says. “I was the only person in the theatre at the time—as you know, the wardrobe people are the first to come in and the last to leave the theatre. I couldn’t believe my eyes: When I realized that the bow tie had moved to the opposite side of the stage, I was in disbelief…I could’ve sworn I saw a blurry image of a person. I was so frightened that I snatched the tie and moved swiftly to put it back in place and left the theatre.” Wilson provides that, on events when she was alone on the theatre late at evening, generally she “would hear things moving around and some faint voices when I would put costumes onstage or pick up laundry off the stage,” and “I would often see images run past me.”

Davis stories that whereas she isn’t conscious of any incidents in recent times, the mischief she did witness continued for a while.

“She kept playing pranks on us,” Davis says. “She disassembled an accordion on me once, like, the blocks and the reeds inside. They were all unscrewed, like all of them were all over the case.” Why does she gender the spirit as a lady? “Everyone’s assuming it’s Mrs. Leslie Carter, because the theatre featured her while she was a star in New York” within the first decade of the twentieth century, when the venue was known as the Belasco Theatre. Davis acknowledges that they’ll’t ensure it’s her, “but the guess is that she’s a performer, because she never messes with the show.” Whatever the problem, “she always fixes it, or we fix it, by showtime. We’ve never actually had a prank that affected the show.”

The Devilish Deacon

When director Mike Ricci, now primarily based in Minneapolis, turned inventive director of an area theatre in North Carolina (which declined to have its identify included on this story) in spring 1990, the receptionist and field workplace supervisor, plus a couple of board members, informed him tales of a priest who allegedly died within the constructing when it was a Baptist church; he had been a deacon who had led the congregation. Since the employees consisted of simply Ricci and the field workplace supervisor/receptionist, Ricci explains, his position was “pretty much of a one-person operation,” with duties starting from funds administration and fundraising to bodily upgrading the house and designing and setting up units. As a end result, he notes, “I spent a lot of hours in that building, from early morning to past midnight on some days.”

On one scorching summer season evening in that first yr, Ricci was alone within the theatre and wanted to get to the sunshine board. He explains that reaching the board on home proper required going throughout the balcony, as a result of the house retained the church format—“pews for seating, stage built over the baptistry, balcony where the lighting booth was set up, stained-glass windows surrounding the audience and backstage”—and had entry to the balcony on simply the home left aspect.

“As I started crossing the balcony,” he recollects, “the temperature suddenly dropped. I got chilled to the bone, and the hair stood up on my arms and my neck. I had never experienced that before. Thinking that it might be the deacon, and that he might be resting up in the balcony, I carefully made my way over to the light board, made the adjustments I needed to make, and made my way across, and then back down the stairs and onto the stage.” When he resumed his work, Ricci says, “I began to feel very uncomfortable, almost like a weight on my chest, difficulty breathing, etc.” He stood up and introduced, firmly and clearly: “I know you’re here, Deacon, and I’m sorry about what’s happened to you. But I have work to do, and I’m going to be spending a lot of time in this building, so let’s make a truce that the both of us can be in here at the same time without bothering each other. Okay?” Ricci says he paused a bit, then “began to feel more normal—the weight was gone, and my breathing returned to normal.” After that, Ricci says, “I always felt that I had made some kind of peace with the deacon, and we were able to coexist in the building without really getting in each other’s way.”

Apparently the truce didn’t lengthen to Ricci’s spouse and daughter. About a yr after that incident, Ricci’s spouse, painter and designer Ellie Ricci, was engaged on the corporate’s 1991 manufacturing of Frankenstein, and stories a weird expertise whereas she was washing off brushes. She says she went to the again of the constructing to the slop sink; to take action, due to the church setup, it was essential to go down a hallway to the store, and on the reverse finish of the store was a small room with a sink. “I went down the hallway—nobody else was around at the time—walked past the shelves on my right that went over my head about a foot or so,” she says. On the nook publish of the highest shelf was a corduroy Florida State baseball cap. “It was sitting on top of that post for a very long time, years, I’d say. When I walked past it and got to the back where the door to the sink was, I heard something drop behind me. I turned around and it seemed that the hat was dropped to the floor. But in order for that hat to come off that peg it would have had to be lifted and dropped, and it was dropped right side up onto the floor.” She regarded round, known as out, and when nobody responded, she proceeded towards the sink.

With her again to the door, she says, she “kept turning around because I kept thinking there was someone behind me, maybe wanting to use the sink, I don’t know, but nobody was there. I washed up as quickly as I could because I started getting the creeps.” She headed again to the theatre, put the cap again on the publish or on a piece desk, “walked out the door and started walking down the hallway. Then in my ear, very close to the back of my head, at my right shoulder I heard a big hiss that was too close for comfort, so I screamed and ran back to the stage. Needless to say, I was pretty rattled.”

Their daughter, Danielle Ricci, now a choreographer, director, and educator, was 8-10 years outdated throughout Mike Ricci’s tenure on the theatre and attended elementary college throughout the road from the theatre. She hung out there every day after college whereas her mom was at work. “As a kid I grew up with a gift of feeling energy and hearing things,” she recollects. “I didn’t like it, because it scared me and made me uncomfortable.” She notes that she’s an solely little one, “so I was left to myself at the theatre and would find ways to fill the time as my dad either worked in his office or in the shop building a set. There were many times where I felt that I was being followed—especially on the stairways on either side of the building.” She describes how she’d climb the steps “in a weird way so that my back was against the wall so that I didn’t feel the presence behind me.”

A number of recollections significantly stand out, she says. “There was a time in which I was sitting and drawing in the break room and was hearing my mom’s voice call me from the shop area of the theatre,” she says. “I knew my mom was at work and thought it was impossible that she was there. But I keep hearing my name being called. So, I called her from the phone on the desk I was sitting at, and she was in fact at work.”

Then there was the time her college choir was studying a musical theatre medley that included the title tune of The Phantom of the Opera. “There was a day where I was in the lobby by myself, singing this part of the concert to myself,” she recollects. When she acquired to the Phantom’s line “Sing, my Angel of Music!” she says, “I heard these disembodied words right behind my right ear as clear as day.” She was so upset, she says, “I ran out of the room trying to find my dad.”

On one other event, she was in her father’s workplace, which had beforehand served because the deacon’s workplace. She explains that her dad’s “desk sat facing the door, and a wall of windows was to the right. There was a heavy window that was always propped up with a piece of scrap lumber cut to hold the window open.” As she sat on the desk, “filling my time, I saw the top of the piece of wood forcefully drop out, causing the window to slam on the wall. There was a loud sound like the furnace roaring, and the chair I was sitting in spun around.”

In sum, Danielle says she was all the time uncomfortable on the theatre as a result of the deacon’s presence “was always around me. There are many times I would be in a room doing whatever I was doing and I would get so overwhelmed with a feeling of his presence that I would go find another person to be with.” Those sensations, she says, “made me aware that the stories about the deacon were very true.”

Voices in My Head

When Bob Shuttleworth was technical director of the Albany Little Theatre (now Theatre Albany) in Georgia from July 1984 to August 1986, he says, he “had heard rumors and legends of encounters at the theatre, a large antebellum home to which a theatre house (stage and audience) had been attached at the rear.” The constructing has been providing performances since 1932, so there’s been loads of time for these tales to build up. “One legend involved a bride who died on her wedding day at the home,” Shuttleworth says. “One co-worker stated that she’s felt a presence pass through her, leaving the scent of lavender behind.” He notes, “I am not necessarily a believer in such things, however I try and keep an open mind.”

On one evening in 1985, at round midnight, he was onstage engaged on a chunk of surroundings for the upcoming manufacturing when one thing weird occurred. “I began to feel something,” he recollects. “Something intangible. I tried to simply shake it off, but it didn’t stop. A few minutes later I noticed that the stage had grown noticeably cooler, and that the feeling that something was there with me grew stronger.” He was kneeling on the stage on the time and raised his head to go searching, however there was nothing to be seen. “Then I began to feel nervous, even a bit shaky, but couldn’t figure out why. That’s when I heard something. Or actually, I felt something, some kind of a voice in my mind. It was saying to me, ‘You need to leave…now!’ It was calm, but insistent. I laid down the tool I was holding and stood up and again looked around. Then I felt the presence again saying, ‘Now!’”

Shuttleworth explains he left the device, turned off the lights, and headed out the door, locking it behind him. “As I took the few steps to my van, I began to feel calmer in one way, but definitely unnerved. I truly believed that I had heard/felt something. It definitely motivated me to leave. I worked there for about another year. Never had that experience again.”

The Ghost Light and the Wind Walkers

Though theatre ghosts are sometimes related to outdated, storied venues, Sheila Rocha, chair of performing arts on the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, N.M., stories unusual happenings at her campus’s Performing Arts and Fitness Center (PAFC), regardless that its building was accomplished in 2018. When the PAFC was lower than a yr outdated, she says, “booms were set up for side lighting. LEDs set, tested, and ready. We turned off everything, about to walk out, when a light from the suspension grid faded up.” A member of the tech crew went as much as the catwalk and unplugged the instrument. As all of them acquired prepared to go out, the stage left sidelight turned on. “We’re a bit baffled. Checked the light board—it’s powered off. We unplugged it, but it just remained on. We studied that contraption and all the power cords from every angle. It had no juice but continued to remain lit.” She provides, “We let it be what it was, locked up and went home. It finally went to sleep sometime during the night.”

Rocha highlights that IAIA “is the first tribal college to create a BFA program in Indigenous Performing Arts with a state-of-the-art black box theatre,” and notes that this system’s earlier house was extremely inappropriate for efficiency, a “Navajo-inspired structure on the property” that had “terrible sight lines and support poles, poor acoustics, and this peculiar ambience.”

One time whereas rehearsing with an Acting 1 class, “we were struggling to block inside of four major support beams. We sat on the floor to brainstorm our dilemma. Without warning the skylight turned dark as apparently storm clouds began to gather above us.” Rocha continues, “A powerful wind fell upon the hogan, subsided, and then we heard the oddest sound of footsteps. On the roof of the hogan we heard someone or something walking. They moved over the roof from one side and then to the other. A second set of footsteps joined in.” She provides, “We peered upward but saw nothing through the skylight. Steps intensified. The apparent weather change became too much for us, so we decided to light a fire in the wood stove. One of the acting students picked up a few logs and opened the stove.”

They then heard the wooden drop to the ground. “Everyone turned to see the student standing in bewilderment as they backed away. Another student jumped up to see what was in the stove.” What did they discover? “A small multicolored bird lay dead inside. It wasn’t a native species from the area. But it lay there spread out as if someone had designed its presence—one wing opened like a fan. The other wing tucked gently behind the tiny body, its beak closed pointed upward. An art piece with no purpose.” One scholar fastidiously took out the hen and introduced that he’d bury it exterior. “He left the hogan, a gust slamming the door shut behind him. The wind whipped up once more.”

They all went to the middle of the constructing, in settlement that one thing was deeply off however not understanding what to do. “As quickly as the wind and footsteps arrived,” Rocha says, “they abruptly subsided. The sun broke through the gray, and whatever was walking above our heads relented. The student returned, and like good theatre folk we went back to work, but with eyes on the clock.”

Rocha additionally recollects an eerie expertise in round 2005 at a theatre in Nebraska (which requested to not have its identify included on this piece): “Our Native American ensemble, Four Directions, rehearsed and performed in what used to be the theatre balcony,” Rocha says, “transposed into a black box with subtle reminders of its century-old Mediterranean and Moorish architecture.” She continues, “During the Jim Crow era, it consigned people of color to the balcony, but later became the more contemporary locus for communities of color to explore performance creation. Mortar holds memory.”

During a break, one of many actors, named Moses, went to the basement to get chilly drinks for the group. Rocha says he heard him shout, “Come down here right away!” She says she took the elevator down and stopped in entrance of the fireside within the former smoking room. “I didn’t see Moses,” she says, “but I heard the sound of a bouncing ball from the basement lobby area.”

“Moses?” she stated in a stage whisper. “Moses, are you down here?” Rocha notes that it was chilly within the basement, and the lighting consisted of a faint yellow from sconces on the partitions. “I heard heavy feet walking across the mosaic flooring. The bouncing faded as if the ball rolled away. ‘Moses!’ Stage voice two. I’m feeling a little creeped out now. I moved toward the light.” The actor responded: “‘Dang, did you hear that?’ My tall Lakota colleague, along with his arms pushed deep into his pockets, emerged from across the nook—his eyes vast. ‘You see anything? But you heard it, didn’t you?’ Rocha says she may do nothing however nod.

Rocha says that though “Moe’s a grown man and a leader in the community,” that evening “he shook his head, accompanied by a nervous chuckle, half unnerved. His long braids trailed behind him as he cued me to start up the stairs with him.” She continues, “I tried to ask about the drinks, but having lost all interest he hustled up the steps, his boots clicking the speed of hooves at a steady gait. As we reached the main landing we heard a sound, like a door closing or opening from below—and that damned ball, or was it air ducts, or a rat?” She provides, “We froze, looked at each other for a split second, then ran up the next flight of stairs laughing, or screaming—stage voice three, who knows. All I recall is that we were alarmed, and it was all I could do to keep up with him. The theatre was mostly dark until we reached the mezzanine.” She recollects saying, “Yes, I heard it. But I didn’t see anything, and you didn’t either, did you?”

She says he defined that, upon reaching the highest of the basement stairs, Moses heard a toddler’s voice and the sound of a bouncing ball. “He called down to see what child might be there, if perhaps someone was still in the building. Youth classes rarely extended beyond our evening rehearsal time three floors below us and tucked away. No one answered him. But he continued to hear the bouncing ball and kid sounds, so he decided it was best to see if someone, somehow got locked in the theatre.” When he discovered the house empty, he known as out to her. “But I got here in from the course that he had heard the voice and it was solely the dim chilly—nobody was there.

“We hopped the elevator from the mezzanine to avoid any unnecessary encounters with the mystical,” she says. When they reached the black field, two of the youthful performers, accompanied by two older actors, “approached me as the director to describe how they had been mysteriously accosted. One child’s braid was pulled by…no one; an older teen in a back room saw someone open her door while she was changing, but no one was there.”

Rocha describes what occurred subsequent: “As our Indigenous ways instruct us, we did the appropriate ceremony and prayer to address the tricky spirits who came to taunt us,” she says. “We were able to get them to leave that evening, but other rehearsals for other shows opened new portals for supernatural guests who took their turns invading our spaces: shadowy figures watching us from empty audience seats, voices muttering in other languages, and an occasional tittering child reminding us the sacred can equate to the unknown.” Rocha repeats: “Mortar holds our memories.”

Russell M. Dembin (he/him) is a former managing editor of this publication.

Related

[ad_2]