[ad_1]

Dan Sullivan, longtime theatre critic for the Los Angeles Times in addition to the previous director of the Eugene O’Neill National Critics Institute, died on Oct. 4. He was 86.

“If the play seems at times incoherent and tedious, the reviewer will mention the heresy that this may be more the fault of the author than of the director.”

The play? Hamlet, no much less. The reviewer? Dan Sullivan, no much less. The manufacturing? The 1963 opening of the Guthrie Theatre, no much less.

Most of us critics have a tendency to depart Hamlet alone, on the grounds that its bona fides are—effectively, because the Supreme Court would possibly say (or as soon as would have mentioned), settled legislation. Safer responsible the manufacturing.

But not Sullivan.

“Hamlet is a great poem, trapped inside a bulky melodrama, and you can’t cut the melodrama without hurting the poem,” he wrote for the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. He had some extent, and, the identical overview reminds us, a neat means with phrases: “’Great’ is the word for Ellen Geer’s Ophelia. The girl shows backbone in her early interview with the prince (‘Indeed, my lord, you made me believe so’ is delivered without the customary whimper) and in the mad scene she is actually mad. Hair in dirty disorder, gown stained with grass, she falls to her knees with a sob and claws the floor of the palace with her fingernails.”

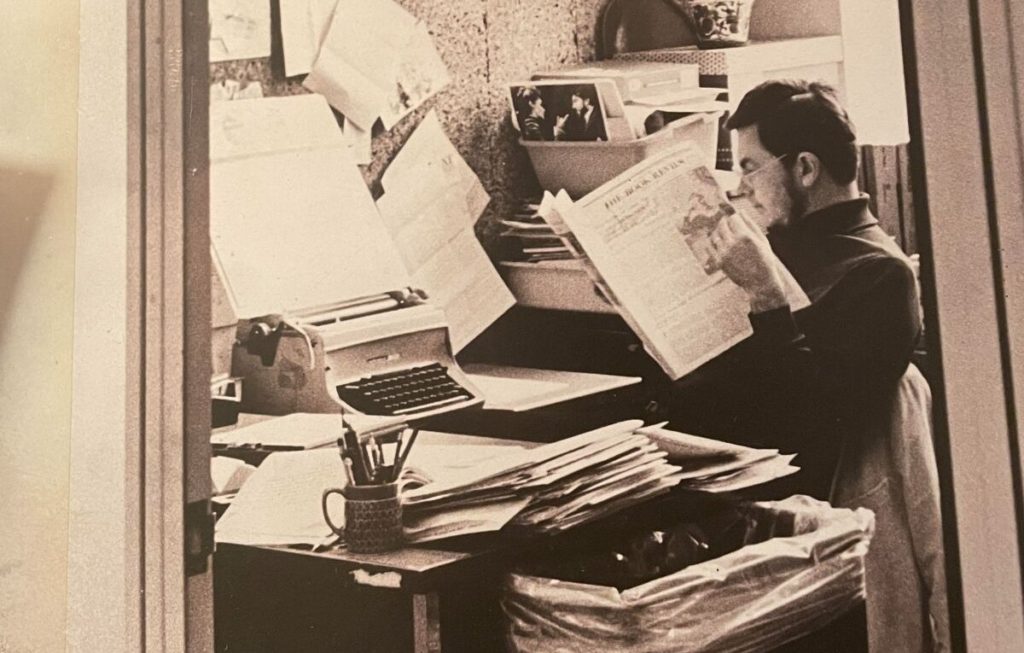

The fashion is authoritative, descriptive, fearless, clipped, third-person, unconcerned with the niceties of psychological well being; certainly, given our present period of essentially self-protecting critics, you wouldn’t learn such a paragraph at this time. But Sullivan got here from a distinct period, one through which hedging was as a lot an indication of weak point as a run-on sentence or an over-reliance on adjectives. He didn’t usually use first particular person—few of his friends did—and would have minimize “I feel that” and its relations, not that such phrases would ever have discovered on their means from fingers to typewriter to printed web page.

Sullivan variously wrote for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, Minneapolis Star-Tribune, New York Times (for whom he coated Off-Broadway), and, most notably, the Los Angeles Times, the place he labored for 22 years, a lot of it locked in a fierce essential rivalry with Jack Viertel. This geographic vary meant that Sullivan didn’t include the everyday New York parochialism of his career, although he actually wrote within the fashion of the large metropolis newspaperman (or, within the case of the Chicago Tribune‘s infamous Claudia Cassidy, newspaperwoman). The lede was the lead; it was not the critic clearing their throat. Fancy phrases had been to be eschewed (so had been parentheses). Clarity was a creed, spelling errors a curse. Paragraphs so long as this one had been pushing their luck.

For his technology of critics, opinions weren’t a contract task however a beat, as common as a sports activities columnist, whom such critics usually resembled. Reporting what was on view was the primary obligation. Verbs wanted to be robust. Prepositions shouldn’t finish paragraphs. Nouns had been your pal; descriptive adjectives had been far simpler than meaningless qualitative expressions of reward like “excellent” or, worse, “really good.” And writing on deadline was a muscle that needed to be saved in form by going to a type of author’s gymnasium of the thoughts. Delay simply meant extra blather.

Above all, Sullivan believed, the critic served the viewers. Not the actor unable to face the reality. Certainly not the nervous producer. There was no obligation to be supportive of the theatre, and a sure Anton Ego-like theatrical flourish down the aisle was acceptable, even when Sullivan was, like many (however not all) critics, an introvert.

Improbably, maybe, Sullivan was totally devoted to instructing younger critics, which is how I got here to know him once I took over the National Critics Institute on the Eugene O’Neill Center a couple of years in the past. I inherited a submitting cupboard with yellowed notes, and even Sullivan’s longtime affiliate, the gregarious theatre professor Mark Charney, who liked Sullivan, who may very well be gruff, like a brother. The cupboard turned out to be considered one of nice curiosities for anybody within the mild artwork of theatrical reviewing: a bevy of recommendation for cultural writers may very well be discovered within the drawers therein, with a selected specialty in methods for dealing with the dreaded urgent deadline and the stubbornly empty web page.

Sullivan, who had continued on the O’Neill, which he liked, effectively previous the standard retirement age, clearly discovered it exhausting for one more to take over his place. I’m sufficiently old now to raised perceive that—I imagine Edward Albee referred to as it the 360-degree view, the place you’ll be able to see each your youthful errors and what lies forward—however he was nonetheless gracious and supportive, particularly as soon as he understood that adjustments in this system, and its fashion, had been wanted to maneuver with the instances. Sullivan didn’t have to show folks how you can cope with hateful collective assaults on Twitter and Facebook.

But we’ve saved a lot of what Sullivan put in place: writing on in a single day deadline, a flurry of exercise, forthright dialog on what it means to be a critic, which obligations to take significantly and which to disregard, regardless of how a lot strain comes your means. And we nonetheless attempt to assist of us proper nice first paragraphs, to affix them effectively to what follows thereafter, and to finish with a heck of a kicker. The place nonetheless could be very a lot him, even when nearly all the things about theatre criticism has fully modified.

As somebody who has learn extra of his work than most, I’ll finish with this: Dan Sullivan was extremely good. He didn’t a lot overview theatre as wrestle with it.

(A good kicker—if solely it ended with a stronger noun.)

Chris Jones is the longtime theatre critic for the Chicago Tribune and the Broadway critic for the New York Daily News. He now additionally serves as editorial web page editor for the Tribune. He wrote for American Theatre for a few years, however that is his first piece for the journal shortly.

Related

[ad_2]